Storing and shipping natural gas by trapping it in ice with technology being developed by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) could cut shipping costs for the fuel, making it easier for countries to buy natural gas from many different sources, and eventually leading to more stable supplies worldwide.

The DOE researchers say the approach could also be safer than current methods of shipping natural gas, such as cooling it to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG), since there is no danger that iced natural gas will explode if the shipping container is damaged.

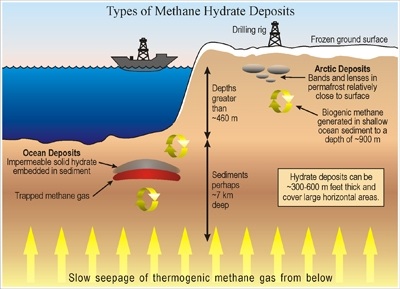

The technology traps natural gas in the form of methane hydrate in which methane, the main component of natural gas, is confined within cage-like ice crystals. Conventional technologies for making methane hydrate take hours or days: they involve mixing water and the hydrocarbon in large pressurized vessels.

The new approach forces water and methane through a specially designed nozzle that creates the methane hydrate “almost instantaneously,’’ said Charles Taylor, the lead researcher on the project at the DOE’s National Energy Technology Laboratory in Pittsburgh, Pa. As the mixture exits the nozzle, it quickly forms hydrate, which looks like snow.

The challenge, Taylor said, was designing the nozzle to create precisely the right conditions for forming the methane hydrate immediately after the mixture of water and methane exits the nozzle. If the hydrate forms too soon, it clogs the nozzle. Although the approach has only been demonstrated at a small scale, it could prove cheaper than existing transportation methods, he said.

Enjoying our insights?

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up with the latest industry trends and developments.

Stay InformedThe difficulty and costs of transporting natural gas — either through pipelines or by converting it to LNG – means many natural gas resources, particularly remote ones, are too expensive to access. Taylor said the new technology could help rescue some of these “stranded” resources, increasing worldwide supplies and allowing more countries to become producers.

The results of a methane hydrate demonstration project in Japan by Mitsui Engineering and Shipbuilding, a large maker of ships for transporting oil and natural gas, suggested that the total cost of transporting methane hydrate – including the infrastructure required to make it and release the gas at its destination – could be “much lower than that of LNG,” according to the company. That demonstration used conventional methods for making methane hydrates, Taylor said. His new technology would make the approach even cheaper, he said, although the researchers haven’t yet determined by how much.

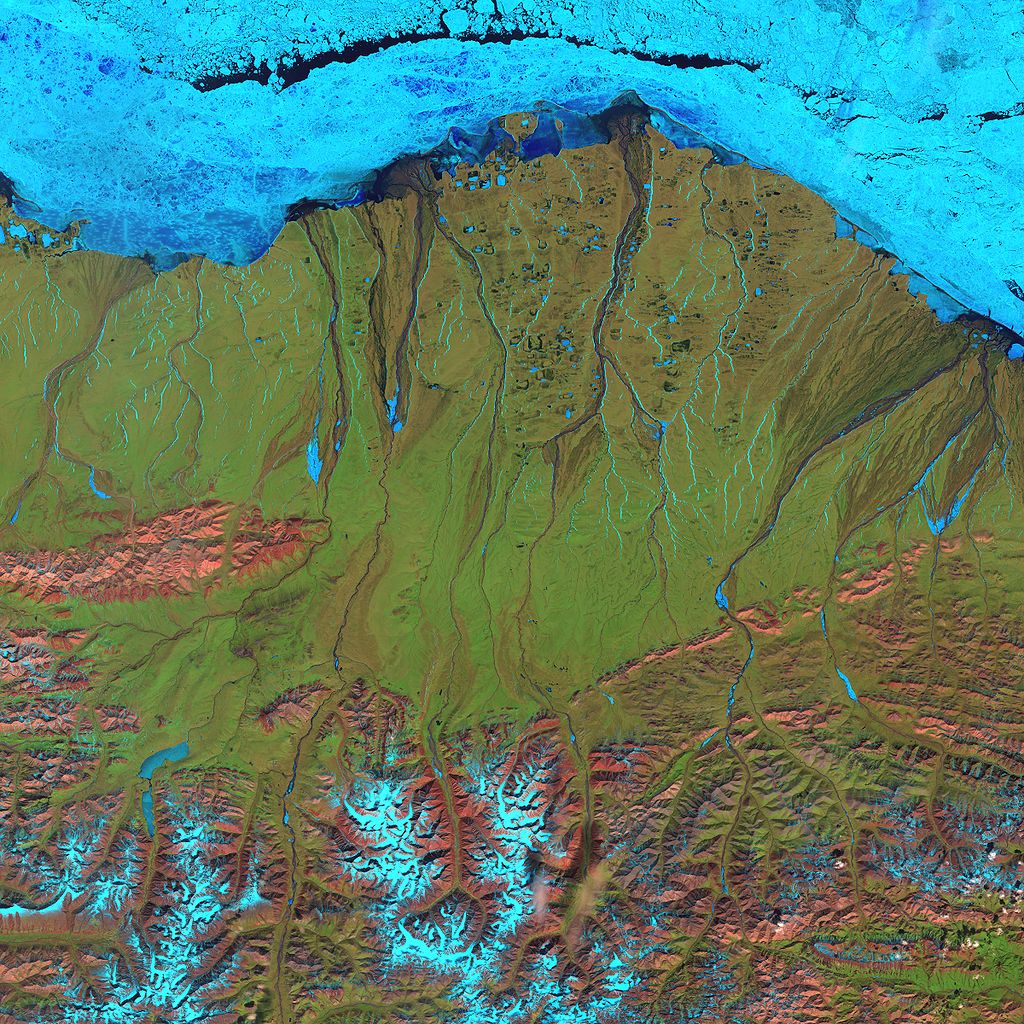

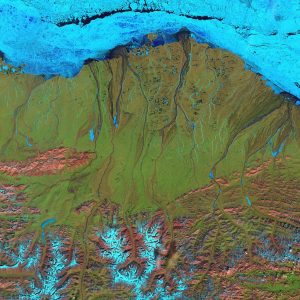

Landsat 7 false-color image of the North Slope. Along the coast, fast ice still clings to the shore in a solid, frozen sheet. At the top of the scene is the drifting sea ice. A dark blue strip of open water, known as a flaw lead, separates the fast ice from the drifting sea ice. The Brooks Range is visible at the bottom. (June 2001)

Making methane hydrate involves mimicking the high pressure and low temperatures at which it forms in nature, typically deep under the ocean. (Huge reserves of methane hydrate exist in places such as the Alaskan North Slope, both threatening to become another source of greenhouse gases and potentially offering a huge source of natural gas.) Once the ice crystals form, they keep the methane confined even if the surrounding pressure is lowered, so the methane hydrate can be shipped at atmospheric pressure as long as it’s kept frozen.

The snow-like hydrate can be packed into cubes and loaded into the refrigerated ships, boxcars, and trucks now used to ship frozen food at minus 10 degrees centigrade (C). That temperature is far easier and cheaper to manage than the minus 162-degree C required for LNG. Also, if LNG shipping containers are damaged, the methane can quickly vaporize and explode. Taylor says that while the methane hydrate can burn, the methane is released slowly enough that it’s not explosive. (If a shipping container were damaged and the hydrates melted, the methane would escape slowly and dissipate before it reached explosive levels. There would be a danger of explosion if the methane were allowed to accumulate in a confined space.) When the hydrate reaches its destination, the methane can be released by letting it warm to room temperature.

“Conceptually, the approach is very interesting,’’ said Anthony Meggs, a visiting engineer at MIT and former vice president for technology at BP. But he said that “it’s hard to tell how practical it will be until you translate it into a cost per ton or cubic foot to transport natural gas.’’ Doing that will require a larger-scale demonstration. He said that if the approach works, it could still take decades to make an impact on worldwide energy markets, because companies will want to recoup their investment for current transportation infrastructure, such as specialized LNG ships and terminals, before investing in new technology.