Driverless Hazmat Trucking: PHMSA’s HM‑266 ANPRM Tackles the No-Driver Scenario

- Driverless hazmat trucking is now a live federal rulemaking issue — PHMSA’s HM‑266 ANPRM spotlights what changes when no trained human operator is on scene (and what tank fleets should prioritize in their comments).

- Electronic shipping papers + emergency response information look like the first high-impact modernization — because first responders and inspectors still need fast, verifiable access to hazmat details when the cab is empty.

- Security plans, cybersecurity, and hazmat employee training are likely to extend beyond the driver — toward remote operations centers, telematics workflows, and clearer “who is accountable” definitions that over-the-road tank stakeholders can shape now.

PHMSA is gathering industry input in HM‑266 on how hazmat compliance should work in highly automated transportation systems.

Driverless hazmat trucking has moved from concept-stage debate to an active federal regulatory question — and PHMSA is now openly asking how the Hazardous Materials Regulations should function when there may be no human operator at the scene. That single change ripples through nearly every “routine” hazmat assumption: who presents shipping papers, who secures a scene, who detects a developing leak, who communicates with first responders, and who is accountable for actions that used to be performed by a trained driver at the equipment. For more news and updates on PHMSA’s regulatory initiatives, see our PHMSA coverage.

PHMSA is gathering industry input in HM‑266 on how hazmat compliance should work in highly automated transportation systems.

PHMSA’s December 4, 2025, Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) is not an approval of autonomous hazmat operations. It is also not a ban. It is, however, a clear signal that driverless hazmat trucking is being evaluated in the same regulatory frame as drones, delivery robots, and other highly automated transportation systems — and that the agency is mapping where the current rules rely on human presence, where they can be modernized, and where safety expectations may need to rise rather than relax. For additional insights into this ANPRM and related regulatory moves, visit our ANPRM archive.

For tank truck carriers, shippers of bulk liquids, third-party logistics firms, and the technology companies building automated driving systems, the practical takeaway is simple: the government is inviting detailed, operationally grounded input right now. Comments on Docket PHMSA‑2024‑0064 (HM‑266) are due March 4, 2026. The quality of those comments will influence what PHMSA proposes later — and how quickly the industry sees movement on electronic documentation, remote emergency response information access, security plans, training definitions, and loading/unloading controls. To stay current on coverage tied to day-to-day tank operations and regulation, see our TankTransport reporting.

Enjoying our insights?

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up with the latest industry trends and developments.

Stay InformedDriverless Hazmat Trucking and PHMSA’s HM‑266 ANPRM: The Practical Landscape

PHMSA’s ANPRM is framed around “highly automated transportation systems,” explicitly spanning an automation spectrum from small robotic systems to large freight vehicles. This matters because it shows how PHMSA is thinking: they are trying to build regulatory concepts that can scale across modes and platforms while still landing in the real world of 49 CFR compliance.

At its core, the ANPRM asks: What parts of the Hazardous Materials Regulations (HMR) implicitly assume a human is present, and what does “equivalent safety” look like when that assumption is removed? For over-the-road bulk transport, that becomes a direct question about autonomous trucks and tankers, remote supervision, incident response timing, and enforcement. For more insight into coverage tied to regulatory interpretation and compliance implications, see our HMRs coverage.

PHMSA is also signaling cross-agency coordination. In practice, driverless hazmat trucking will not be governed solely by PHMSA. PHMSA governs hazmat classification, packaging, hazard communication, documentation, training, and security planning. FMCSA governs much of the operational safety framework for interstate trucking and the commercial driver context. NHTSA influences vehicle safety design norms (and may become more consequential if safety standards for automated driving systems evolve). TSA influences aspects of transportation security planning. And at the edges, states influence what is allowed to operate on their roads, even when federal rules set baselines. For additional context on federal trucking oversight and safety requirements, browse our FMCSA coverage.

When a hazmat truck has no driver to hand over paperwork, responder-ready information access becomes a first-order safety requirement. The ANPRM approach is therefore best read as a systems question, not a single-rule tweak. If the industry wants a workable path, the system has to work end-to-end:

When a hazmat truck has no driver to hand over paperwork, responder-ready information access becomes a first-order safety requirement.

- An “offeror” prepares a compliant shipment.

- A carrier accepts, loads, and transports it.

- Enforcement can inspect and verify compliance.

- First responders can access accurate information in seconds.

- Security controls reduce both physical and cyber risk.

- Packaging and operations lessen the probability and consequences of releases.

- A transparent chain of accountability exists when something goes wrong.

That is the bar PHMSA is implicitly setting for driverless hazmat trucking: not novelty, but demonstrable operational safety and enforceability.

What does driverless hazmat trucking change for tank carriers, shippers, and responders?

A helpful way to think about driverless hazmat trucking is to separate what changes from what does not.

What does not change: Hazardous materials remain hazardous. The public’s tolerance for risk remains low. The consequences of a release from a tank trailer remain potentially severe, especially for flammables, toxics, and corrosives. Packaging integrity, loading discipline, route risk, security planning, and accurate hazard communication still determine safety outcomes. For additional reporting on hazardous materials transportation risk and compliance, see our Hazmat coverage.

What does change: The safety model shifts from “trained human present + regulated processes” to “regulated processes + technology-mediated awareness + remote human oversight (maybe) + engineered fail-safes.” That shift stresses the HMR in predictable places:

- Shipping papers and emergency response information: The rules historically assume a driver can present documentation on demand.

- Hazard communication: Placards still matter, but responders also rely on human confirmation, context, and immediate verbal exchange.

- Training: The definition of “hazmat employee” is straightforward when there is a driver; less so when functions are distributed across remote staff, loaders, dispatch, and software.

- Security plans: Remote connectivity increases cyber risk. Unattended equipment increases physical risk.

- Loading/unloading: Driver involvement varies by operation today; future operations might eliminate that involvement, forcing facilities to absorb new tasks or automate them.

- Enforcement and inspections: Roadside interactions assume a human can comply with an inspector’s instructions.

PHMSA’s ANPRM is less about “allowing autonomy” and more about identifying the human-dependent compliance steps that must be rebuilt as technology-dependent compliance steps, without weakening enforcement or emergency response.

Most near-term progress will come from changes that also help conventional fleets. Electronic shipping papers, better incident notification, stronger cybersecurity requirements, and standardized data formats improve safety for every hazmat move, not just autonomous ones. That is why many observers expect early regulatory movement in data and documentation before movement in full driverless operations.

Driverless hazmat trucking: What PHMSA is asking in the ANPRM

USDOT’s PHMSA is exploring how hazardous materials rules may need to adapt when commercial vehicles operate without an on-scene driver.

USDOT’s PHMSA is exploring how hazardous materials rules may need to adapt when commercial vehicles operate without an on-scene driver.

PHMSA’s ANPRM (HM‑266) sits in the HMR ecosystem (49 CFR Parts 171–180) and asks stakeholders to identify regulatory barriers, safety gaps, and workable modernization options for highly automated transportation systems. For hazardous transport stakeholders, several question clusters matter more than others because they are unavoidable if a cab is empty.

1) Special permits as the near-term bridge – PHMSA acknowledges that innovators have historically used special permits to conduct operations that do not cleanly fit existing rules. The special permit pathway effectively acts as a “controlled exposure” mechanism: PHMSA can allow limited, monitored activity while gathering evidence. For driverless hazmat trucking, special permits are likely to remain a key bridge while the agency evaluates more permanent rules.

For industry players, that means two practical choices:

- Treat special permits as a temporary workaround and wait.

- Or treat special permits as a design constraint and build operations that can be safely permissioned and audited.

A detail worth emphasizing: special permits are not just paperwork; they are a forcing function. They push operators to define controls, reporting, and limitations precisely enough for PHMSA to evaluate.

2) Shipping papers and emergency response information without a driver – PHMSA is explicitly probing what happens when there is no one to hand an officer or firefighter a document packet. This is one of the most immediate and solvable problems, and therefore one of the most likely early areas of regulatory change.

The operational reality for tank fleets is blunt: if a driverless tractor-tank combination is involved in an incident, the responder’s first minute is about hazard identification, isolation distances, ignition sources, and exposure risk. If the load is misidentified, everything downstream can worsen. So PHMSA is pressing for solutions that maintain speed, accuracy, and security of information access.

3) Hazard communication when the “human explanation layer” disappears – Placards and markings remain a core external safety layer. Still, responders often rely on a trained driver to confirm details and explain status (e.g., “no leak observed,” “valves closed,” “product is stabilized,” “vapor cloud present,” “I shut off pump”). In driverless hazmat trucking, that information has to come from somewhere else: sensors, remote operators, or incident notification systems. PHMSA’s questioning points toward a world where hazard communication becomes partly physical (placards) and partly digital (trusted, immediate data access).

4) Training and the redefinition of who is responsible – PHMSA’s hazmat employee training regime is foundational. Automation does not eliminate human responsibility; it redistributes it. A remote operations center employee supervising autonomous trucks might, for particular duties, become functionally analogous to a driver. A dock operator may become responsible for tasks a driver used to perform. Even software changes might need human sign-off in a safety management system.

This raises a practical question that the ANPRM effectively asks: Who counts as the hazmat employee in a distributed autonomous operation, and what training do they need to meet the spirit of the HMR?

5) Security plans and cybersecurity – PHMSA’s security planning requirements already exist for specific materials and operations. Automation tightens the loop between security planning and cybersecurity. If an automated driving system or remote communications channel is compromised, the risk profile changes. PHMSA is signaling openness to revisiting expectations for security plans in light of remote connectivity and unattended operations.

Cybersecurity is not just IT. It becomes part of hazmat safety engineering. A hacked vehicle carrying hazardous materials is not a generic cyber event; it is a potential public safety incident. For more reporting tied to cyber risk, operational resilience, and connected-fleet exposure, see our Cybersecurity coverage.

6) Packaging, loading, and unloading as “system interfaces.”

Bulk hazmat moves still hinge on packaging integrity and hazard communication — PHMSA is now evaluating how those pillars translate to automated operations.

Bulk hazmat moves still hinge on packaging integrity and hazard communication—PHMSA is now evaluating how those pillars translate to automated operations.

Tank packaging standards and loading/unloading procedures are not abstract; they are where releases begin. In conventional operations, drivers often serve as a procedural checkpoint. Remove that checkpoint, and the facility or automated equipment must absorb it. PHMSA is asking where the current rules assume human verification and how that should be replaced.

This is the area where stakeholders can provide the most valuable “ground truth,” because tank loading practices vary widely by commodity and facility. If the endgame is driverless hazmat trucking, then the entire transfer process must be designed for safety, assuming no experienced driver is present to notice abnormalities, stop a transfer, or intervene.

Driverless hazmat trucking: Which hazmat pillars break without a human?

PHMSA’s ANPRM effectively spotlights a set of “hazmat pillars” that are stable in human-operated transport but become fragile in an autonomous environment. For an industry-insider audience, it helps to describe these pillars as specific, testable failure modes rather than general topics.

Pillar A: Documentation access and authenticity – A responder needs the correct information fast. An inspector needs verifiable compliance evidence. A carrier needs a record that survives litigation. A shipper needs assurance that the right product is declared and handled. If the documentation is digital, you must solve: access control, offline resilience, authenticity, and auditability.

Pillar B: Scene stabilization – In traditional discussions of driverless hazmat trucking, people jump straight to collision avoidance. But hazmat outcomes often hinge on what happens after the vehicle stops moving: the first minutes of scene control, ignition source management, establishment of the isolation perimeter, and leak confirmation. A driver often does some of this by training and instinct. Without a driver, the system must provide a substitute: alerting, remote assessment, clear responder interfaces, and safe states (valves, brakes, shutdown).

Pillar C: Role clarity and accountability – Who is responsible for ensuring the shipping paper is accurate? Who is responsible for hazard communication? Who is responsible for monitoring an abnormal condition mid-route? If multiple humans touch the operation across time and distance (shipper, loader, remote supervisor, safety manager), PHMSA will need an enforceable accountability model. Industry can either help define that model now, or risk having a model imposed later that does not match operational reality.

Pillar D: Security resilience – Hazmat security planning has traditionally focused on theft, diversion, and misuse. Automation adds remote access pathways and software dependencies. The security pillar becomes a joint physical-cyber domain: cameras, locks, geofencing, command authentication, incident escalation, and tamper detection.

Pillar E: Transfer safety (loading/unloading) – Bulk transfer is where minor errors become significant events. If you want driverless hazmat trucking to scale, the transfer process must be engineered to prevent wrong product loading, wrong compartment loading, overfill, hose failure, mis-valving, and incompatible connections, without relying on a driver to act as the last manual check.

These pillars are why PHMSA’s ANPRM is a big deal to tank transportation: it invites the industry to say, in detail, how to rebuild each pillar.

Driverless hazmat trucking: How could electronic shipping papers and ER info work?

Electronic shipping papers are often discussed as a convenience upgrade. For driverless hazmat trucking, they are closer to a prerequisite. But “electronic” is not a single design; it is a set of architectural choices with safety consequences.

A practical, enforceable approach tends to include several features:

1) Multiple access paths (because networks fail) – If a responder must access emergency response information, the system should not depend on a single cellular carrier, cloud provider, or device. Industry comments that propose resilient access, such as cached information in a secure onboard module plus a remote database, are more credible than comments that assume always-on connectivity.

2) Authentication and least-privilege access – A significant objection to naive digital shipping paper concepts is that they could expose sensitive information to unauthorized parties. If a system allows anyone to retrieve detailed hazmat data via a simple QR code, it may increase security risks. A more balanced approach is role-based access: first responders and inspectors can obtain details quickly through verified channels, while the general public can only see limited hazard class indicators already available on placards.

3) Fast retrieval under stress – In real incidents, responders do not want an app that requires multiple logins, multi-step navigation, and perfect connectivity. The winning design will be the one that works in gloves, rain, smoke, and noise.

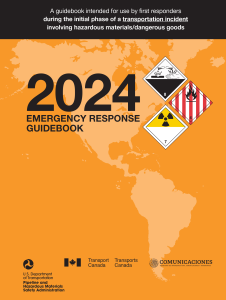

4) Clear mapping to the Emergency Response Guidebook model – Responders often think in ERG terms: ID number, guide number, isolation distances, and immediate hazards. Electronic emergency response information should mirror how responders actually operate, not how shippers store data.

5) Audit trail and legal defensibility – For compliance and post-incident investigations, digital systems should log who accessed shipping information, what changed, and when. If a shipper updates a shipping description, the platform should retain the full revision trail so inspectors and investigators can verify exactly what was available at the time of transport.

Electronic shipping papers also solve a practical gap: they can speed first-responder access and reduce documentation errors across conventional fleets, while also enabling the unique requirements of driverless hazmat trucking**.

Driverless hazmat trucking: How will emergency response and scene control work?

This is the “hard part” that separates a plausible policy conversation from a marketing narrative.

Driverless hazmat trucking policy ultimately gets measured at the scene: responder access, secure shutdown, and clear accountability when something goes wrong.

Driverless hazmat trucking policy ultimately gets measured at the scene: responder access, secure shutdown, and clear accountability when something goes wrong.

If a driverless tank truck is involved in a crash, several questions arise immediately:

What alerts first responders — automatically and with enough detail?

A driver typically calls it in. Without a driver, the system must detect abnormal events and trigger a notification. A credible model may include automatic crash detection, rollover detection, valve position sensors, pressure/vacuum monitoring, and leak detection tied to an incident notification workflow.

Who communicates with responders in real time?

A remote operations center could provide a communications bridge. But that only helps if responders can reach it quickly and it has actionable information, not generic scripts. You can position the remote operations center as the “digital driver,” but then training and accountability become central.

How does the vehicle enter a safe state?

In a conventional operation, a driver may shut down the engine, set the brakes, and close the valves. In driverless hazmat trucking, you need engineered safe states: automatic shutdown logic, protected emergency stop functions, and perhaps remote disable features designed to prevent misuse while enabling responders to control risk.

How do responders secure the scene if the vehicle can move or behave unpredictably?

If an automated driving system is damaged but still powered, responders need a standard way to confirm the vehicle will not move. Industry often discusses “first responder interaction guides” for automated vehicles; PHMSA’s ANPRM provides a forcing function to align that concept with hazmat realities.

What about secondary risks — fire, ignition sources, or incompatible exposures?

A tank truck incident is not only about the product; it’s about the environment. Many serious hazmat events involve compounded factors: collisions, fires, nearby vehicles, weather, drainage, population density, and time-to-response. Automation must fit that reality rather than pretend it away.

- “How will firefighters get shipping papers if there is no driver?”

- “Who do responders call if an autonomous hazmat truck crashes?”

- “Can an inspector place an autonomous truck out of service?”

- “What happens if connectivity is lost in a remote area?”

Those are not rhetorical questions; they are the operational acceptance tests for driverless hazmat trucking. For more reporting tied to deployment realities and policy friction points, explore our AutonomousTrucks archive.

Driverless hazmat trucking: Technology realities that will shape compliance

Autonomous trucking platforms are advancing — PHMSA’s HM‑266 ANPRM is testing what hazmat compliance looks like when the cab may be empty.

Autonomous trucking platforms are advancing—PHMSA’s HM‑266 ANPRM is testing what hazmat compliance looks like when the cab may be empty. Aurora’s self-driving trucks hit the road in Texas (credit: Aurora)

It is easy to treat this as a policy-only conversation. It is not. The rules PHMSA can credibly modernize depend on what the technology can reliably do under failure conditions.

Several technology realities deserve emphasis, especially for tank stakeholders evaluating partnerships with automated driving system developers:

Reality 1: “Autonomous” rarely means “unattended.”

Many systems operate with layers: onboard autonomy, remote monitoring, and escalation paths to teleoperation or human intervention. From a regulatory standpoint, this matters because PHMSA must know whether there is always a trained human “in the loop,” and what that person’s role is. If remote humans are integral, then hazmat employee training, security vetting, and recordkeeping may need to expand to cover them.

Reality 2: Connectivity is a safety dependency and a vulnerability.

Remote supervision, digital shipping papers, and incident notification all depend on connectivity. Connectivity can fail. Connectivity can also be attacked. A mature safety posture treats communications as both a safety dependency and a security risk, designing redundancy and intrusion resilience into the system.

For driverless hazmat trucking, this is not academic. A loss of connectivity during a typical trip is manageable if the vehicle can safely continue or safely stop. A loss of connectivity during an incident is much harder if emergency response information becomes inaccessible. A compromise of connectivity is harder still if an attacker can influence vehicle behavior.

Reality 3: Tanks create different risk profiles than dry van freight.

Autonomous trucking narratives often center on highway lane-keeping and collision avoidance. Tank transport adds layers: bulk surge dynamics, slosh effects, rollover sensitivity, product-specific hazards, vapor pressure behavior, thermal considerations, and transfer system complexity.

Even if a tractor’s automated driving system performs well, the combined vehicle dynamics matter. A credible industry discussion of driverless hazmat trucking must include tank-specific operating envelopes and whether the ADS is validated for those envelopes.

Reality 4: The “last 50 feet” is where operations get messy.

Highway automation is one thing. Yard operations, gate entry, staging, loading racks, and customer delivery sites are another. Many of the human-dependent tasks in tank transport occur precisely in these environments. If driverless operations are attempted, the facility may need new infrastructure: automated gate systems, defined routes, clear signage, secure staging, standardized interfaces for coupling and transfer, and procedures for abnormal situations.

Reality 5: Enforcement has to remain practical.

Even if PHMSA modernizes HMR requirements, enforcement still needs workable touchpoints. CVSA inspection models, roadside interactions, out-of-service decisions, and documentation verification are all built around a human driver. If enforcement becomes more difficult, regulators will respond either by restricting operations or by imposing new technology requirements that make enforcement easier (e.g., standardized digital compliance interfaces).

Regulators will not trade enforceability for innovation. The more the industry can propose solutions that keep enforcement reliable and straightforward, the more plausible progress becomes.

Driverless hazmat trucking: What should fleets, shippers, and tech firms do now?

PHMSA’s ANPRM spotlights a practical question: how do responders get accurate hazmat details fast when there’s no driver to brief them?

PHMSA’s ANPRM spotlights a practical question: how do responders get accurate hazmat details fast when there’s no driver to brief them?

The ANPRM stage is where PHMSA is collecting raw operational data, precisely the kind of information tank fleets can provide better than anyone else.

As HM‑266 develops, the most consequential stakeholder input tends to be operational: specific scenarios, measurable safety outcomes, and enforceable controls. For OTR tank stakeholders, the themes below are most likely to shape what PHMSA can credibly modernize — and the conditions that could attach to any future automated hazmat moves.

1) Define “no human present” scenarios and the minimum control set – Driverless hazmat trucking raises predictable “no on-scene operator” situations that regulators, enforcement, and responders will use as real-world test cases. Examples include:

- Rollover with product release risk

- Minor collision with uncertain leak status

- Disabled vehicle on the shoulder

- Loss of GPS or connectivity mid-route

- Attempted tampering during a stop

- Loading rack abnormal event (overfill alarm, hose rupture)

Across those scenarios, regulators will look for layered controls that are understandable at the scene and auditable after the fact: detection, notification, a defined safe state, a responder-facing interface, and a clear accountability chain.

2) Favor performance-based outcomes that can be verified – Where technology and operating models vary, performance-based requirements can be easier to implement and enforce than a single prescriptive design. In driverless hazmat trucking, this often translates into outcomes such as “emergency response information is accessible to authorized responders within a defined time under degraded connectivity,” rather than mandating a specific platform or vendor architecture.

3) Modernize electronic shipping papers without creating a security exposure – Electronic shipping papers and emergency response information are central to HM‑266 because the driver cannot serve as the “human distribution mechanism” for documents. Any credible approach must balance speed of access with security and integrity. Stakeholder submissions frequently emphasize:

- Access control and authentication for responders and inspectors

- Offline and degraded-mode operation (including caching and redundancy)

- Cybersecurity practices and incident response expectations

- Auditability and record retention (including revision history)

- Standardized data fields that support interoperability

4) Treat remote operations centers as safety-critical functions – If remote personnel will supervise, intervene, or communicate with first responders, regulators are likely to evaluate the remote operations center as part of the safety case — not as a back-office convenience. Expect scrutiny around:

- Training requirements for remote operators as hazmat employees (where duties align)

- Staffing, fatigue management, and escalation coverage

- Authority boundaries and intervention protocols

- Logging requirements for decisions, alerts, and interventions

- Secure communications and access management

5) Address loading/unloading explicitly, with tank-specific operating detail – For bulk liquids, transfer operations are often where risk concentrates, and driver involvement varies by facility and commodity. If driverless hazmat trucking is contemplated beyond limited highway segments, PHMSA and the industry will need clarity on what changes at the rack and at the customer site — especially where drivers currently serve as a procedural checkpoint. Common focus areas include:

- Which tasks shift to facility control versus carrier control

- What automation is already in place (interlocks, overfill prevention, emergency shutdown)

- What additional safeguards are required when no driver is present

- How to prevent wrong-product or wrong-compartment events

- How to manage abnormal events and stop-transfer authority

6) Build for responder and enforcement usability, not just system capability – At the incident scene and during roadside inspections, usability is a safety feature. Regulators and responders will focus on whether information and control pathways are clear, fast, and reliable without a driver. Practical expectations that surface repeatedly include:

- A standardized way to confirm the vehicle cannot move and to place it in a safe state

- Fast, verifiable access to shipping papers and emergency response information

- Clear placarding/identifiers that support digital lookup without increasing public exposure

- Reliable contact pathways to a trained support function (e.g., a monitored operations center)

- Joint familiarization or exercises with local responders where operations are planned

7) Expect phased change: documentation and security first, full autonomy later – Many of the earliest regulatory changes under HM‑266 are more likely to involve documentation, data access, and security expectations — because they strengthen today’s hazmat operations and also address the “no driver with paperwork” problem. Broader permissions or assumptions for unattended hazmat operations, especially involving loading/unloading, are likely to take longer and require clearer evidence and enforceable safeguards.

8) Watch the parallel tracks that will determine real-world feasibility – PHMSA is only one part of the operating environment. FMCSA decisions on operational safety requirements and exemptions, state-level autonomous vehicle rules, and evolving expectations around cybersecurity and connected-vehicle safety can all influence what is practicable, even if hazmat rules modernize. For fleets and shippers planning investments, those parallel tracks are often as decisive as the HMR changes themselves.

Where Driverless Hazmat Trucking Rules Are Headed

Key Developments:

- PHMSA launched HM‑266 (Docket PHMSA‑2024‑0064) via ANPRM on December 4, 2025, formally opening the door to HMR modernization for highly automated transportation systems, including highway freight.

- Comment deadline is March 4, 2026, creating a near-term window for tank fleets, shippers, and technology providers to influence PHMSA’s problem framing before an NPRM is drafted.

- Scope spans the core HMR architecture (49 CFR Parts 171–180), not a single narrow fix, meaning future updates could touch documentation, hazmat employee training, security plans, packaging, and transfer operations.

- PHMSA is explicitly stress-testing “human-dependent” compliance steps, especially:

- Shipping papers & emergency response information when there is no driver to present documents or call for help.

- Hazard communication effectiveness when the “human explanation layer” disappears.

- Training definitions when operational responsibilities shift to remote staff and facility personnel.

- Security plans + cybersecurity as remote connectivity and unattended equipment change threat models.

- Loading/unloading controls where tank-transfer risk is often highest.

- Special permits remain the practical bridge in the near term, signaling that pilots and controlled deployments may continue while permanent rules are evaluated.

- Highway autonomy is being treated as a cross-agency issue, with PHMSA’s hazmat framework intersecting FMCSA operational safety rules and the real-world enforceability needs of roadside inspection and incident response.

- Early regulatory movement is most likely to start with “data and documentation,” because digital shipping papers, authenticated responder access, and standardized emergency response information can improve safety for conventional fleets and enable the prerequisites for driverless hazmat trucking.

- Tank-specific realities are implicitly in play (bulk surge, rollover sensitivity, transfer interfaces, abnormal event handling), making OTR tank stakeholder comments uniquely valuable compared to generic autonomous trucking input.

- Enforcement and responder usability are emerging as acceptance tests, not afterthoughts: any viable approach must keep inspections, out-of-service authority, and incident command workable without relying on a driver.

Explore Official Rulemaking Sources and Technical Guidance on Driverless Hazmat Transport

- Learn more about PHMSA’s HM‑266 Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) and its scope at Federal Register: HM‑266 ANPRM (Dec. 4, 2025). (FederalRegister.gov)

- Track filings, supporting materials, and public input for HM‑266 at Regulations.gov: Docket PHMSA‑2024‑0064.

- Review the primary ANPRM entry and comment instructions at Regulations.gov: HM‑266 ANPRM document record.

- Find PHMSA’s official rulemaking landing page (including the agency “View PDF” pathway) at PHMSA: HM‑266 Federal Register document page.

- Verify the Federal Register metadata (including FR Doc number and docket references) at GovInfo: Federal Register entry 2025‑21970 (HM‑266).

- Understand security plan expectations PHMSA may revisit by reviewing eCFR: 49 CFR Part 172, Subpart I (Safety and Security Plans).

- Access PHMSA’s responder reference hub via PHMSA: Emergency Response Guidebook (ERG) portal.

- Download the current ERG used in early-incident response at PHMSA: ERG2024 (English) PDF.

- Consult FMCSA’s carrier guidance for shipping papers, placards, and compliance at FMCSA: How to Comply with Federal Hazardous Materials Regulations.

- See FMCSA’s waiver cover letter addressing a “no driver on scene” warning-device issue at FMCSA: Aurora warning-device waiver cover letter (Jan. 2026) PDF.

- Review the waiver’s operating terms and conditions at FMCSA: warning-device waiver terms and conditions (Jan. 2026) PDF.

- Explore federal framing of automation safety at NHTSA: Automated Vehicle Safety.

- Review how NHTSA defines and discusses ADS capabilities at NHTSA: Automated Driving Systems (ADS).

- Review security recommendations relevant to highway hazmat movements at TSA: Highway Security Action Items (PDF).

- Examine cyber-physical security considerations for autonomous operations at CISA: Autonomous Ground Vehicle Security Guide.

- Use a baseline cyber risk-management framework for connected operations at NIST: Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 (PDF).

- Clarify automation terminology (Level 0–5) using SAE: Levels of Driving Automation explained.

- See DOT/FAA–PHMSA guidance activity on hazmat by UAS at Federal Register: notice of guidance for transporting hazmat by UAS.

- Read the detailed drone hazmat guidance at FAA: Guidance for Transporting Hazmat by UAS (PDF).

- PHMSA hazmat framework: Review the broader HMR context (49 CFR Parts 171–180) via PHMSA: Hazardous Materials Regulations and resources.

- FMCSA rules hub: Access FMCSA’s centralized portal for rulemakings and compliance at FMCSA: Regulations portal.

- NHTSA automation resources: Explore broader automation material at NHTSA: Automated Vehicles resources.

- FAA UAS hub: Visit FAA’s UAS center for policy context at FAA: Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS).

- Enforcement perspective: Review inspection and enforcement resources at Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance (CVSA).

- Industry insight – NTTC: Explore tanker-focused safety and policy resources at National Tank Truck Carriers (NTTC).

- Industry insight – ATA: Follow trucking policy and technology priorities at American Trucking Associations (ATA).